Using this resource

Nau mai, haere mai. Welcome to He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora, a multi-media resource to support the teaching and learning of te reo Māori.

He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora aims to:

- provide you with resources that will help you to implement a reo Māori programme aligned with levels 1 and 2 of Te Aho Arataki Marau mō te Ako i Te Reo Māori – Kura Auraki, Curriculum Guidelines for Teaching and Learning Te Reo Māori in English-medium Schools: Years 1–13 (Te Aho Arataki), with provision for some extension at levels 3 and 4

- provide you with resources that reflect a research-based, best-practice approach to second-language teaching and learning

- help you to plan your programme for teaching te reo Māori with your students’ whānau

- provide real-life examples on video of students and teachers using te reo Māori in a variety of language tasks

- provide units of work that contain communicative language tasks

- help year 1–6 students improve their ability to communicate in te reo Māori and support them to use the language in everyday situations

- provide opportunities for your students to listen to, speak, read, and write in te reo Māori

- help you use Te Aho Arataki to plan and assess your programme for teaching te reo Māori

- build on the work done in the early childhood sector with Te Whāriki: He Whāriki Mātauranga mō ngā Mokopuna o Aotearoa and prepare students for using Ka Mau te Wehi! in years 7–8

- support you as you give your students insights into Māori values, attitudes, and behaviours by helping you and your students to understand, for example, the tikanga Māori involved in a visit to a marae.

This multimedia resource has three components:

- Teachers' Notes

- DVD (this has been replaced by videos online)

- Website

This planning and professional development material is designed to be used at whole-school, syndicate, or individual teacher level, to help implement Te Aho Arataki. It includes:

- 8 unit plans that promote a task-based approach to teaching and learning te reo Māori (with tasks and activities at different levels of complexity)

- assessment information

- information on second-language learning, the relationship between language and culture, pronunciation, and engaging whānau

- useful classroom language

- references

- supplementary resources

- the video and remations index.

These components serve a dual purpose.

They contain:

- reomations (Māori language animated cartoons to engage your students)

- videos showing students and teachers using the resource in the classroom. The video footage shows students participating in real-life, albeit simulated, tasks that are genuinely interesting and purposeful. This aligns with the communicative approach to teaching and learning te reo Māori, where meaningful communication is the desired outcome.

Website

This website has:

- the Teachers' Notes, videos and reomations

- numerous resource sheets that enable teachers to facilitate the second language tasks suggested in the unit plans

- transcripts of the reomation texts with English translations

- Te Reo Māori in English-medium Schools which contains, among other things, online dictionaries and teacher tools - including lesson plans that align with Te Aho Arataki

- Te Whakaipurangi Rauemi, the online repository for te reo Māori resources on Te Kete Ipurangi

- other online support.

The following key understandings underpin He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora:

- Te reo Māori is an official language and is indigenous and unique to our country. We value it.

- Te reo Māori and tikanga Māori are complementary and interconnected.

- We are all learners. Learning a second language requires us to take risks.

- We use te reo Māori beyond the classroom, in real life.

- There are many benefits to learning te reo Māori.

- Learning a second language is fun.

- Successful second-language learners think about the learning strategies that work best for them. They are autonomous learners.

- Demonstrating a school-wide commitment to learning te reo Māori helps to ensure continuity and sustainability.

- Our education system has a crucial role to play in nurturing and promoting the development of the indigenous language of our country.

- As well as making te reo Māori available to all students, te reo Māori programmes in English-medium primary schools contribute to the Māori Education Strategy, Ka Hikitia – Ka Hāpaitia, which emphasises the importance of the education sector in meeting the needs, aspirations, and expectations of Māori.

Consider the following principles as you plan and implement your teaching programme.

Whānau

- Engage the students' whānau in their children's learning. Base your programme on the needs of your students as determined by their whānau in consultation with you.

- Though the term "whānau" is used in this resource to encompass the families of every student in your class, reflect the aspirations of the local Māori community in what you do and encourage hapū and iwi – and the families of the Māori students in your class – to work with you to share their knowledge and expertise in a productive partnership that advances student learning.

Students

- Encourage your students to initiate exchanges in te reo Māori, for example, when they make requests, ask for help, express confusion or a lack of understanding, and offer praise and encouragement to their classmates.

- Provide your students with good models (input) of te reo Māori in meaningful contexts. Second-language learners benefit from exposure to a wide range of input, including other speakers of te reo Māori, reading material, Māori broadcasts, videos, Māori performing arts, and other cultural experiences.

- Acknowledge and build on your students' prior knowledge of, and experience with, te reo Māori.

- Respect and value your students' backgrounds.

Teachers

- Ensure that learning te reo Māori in your classroom is engaging, fun, and rewarding.

- Have high, yet realistic, expectations of achievement in te reo Māori to accommodate the needs of diverse learners.

- Ensure that the atmosphere in your classroom is one of encouragement to build the students' confidence. Use praise and sensitive correction to address errors.

- Provide specific, constructive feedback/feed forward opportunities to enhance fluency and accuracy.

- Facilitate meaningful tasks and activities that encourage the use of te reo Māori for authentic purposes.

- Promote language learning autonomy. Help your students to formulate their own learning goals in consultation with you. Support them to become self-monitoring and to think about how they can best approach their learning of te reo Māori. Help them to develop strategies that enable them to learn the language more easily.

Programme planning and implementation

- Align your reo Māori programme with the curriculum guidelines, Te Aho Arataki, and with The New Zealand Curriculum (for example, with the key competencies).

- Keep developing your own knowledge and understanding of te reo and tikanga Māori. Working with whānau and other staff members, sharing knowledge and ideas, and supporting one another will make this a lot easier for you. Build on the "teacher as a learner" concept and show your willingness to extend your own knowledge in a spirit of openness. This puts the concept of ako into action in your own practice.

- Provide different entry points. Most of your students will be learning at curriculum levels 1–2, but some may be capable of learning at curriculum levels 3–4. It is feasible that students in both year 1 and year 6 could be learning at curriculum level 1.

- Utilise the other second-language teaching and learning resources that the Ministry of Education provides on Te Whakaipurangi Rauemi.

Tikanga

- Integrate aspects of tikanga Māori into your classroom. For example, demonstrate manaakitanga, include tuakana-teina roles and responsibilities in your classroom, sing waiata together, and take turns to speak.

Second-language pedagogy

- Use a communicative approach. Provide meaningful contexts and real-life situations in which your students have a genuine need to communicate in te reo Māori.

- Plan a balanced programme that includes both receptive and productive skills (listening, reading, viewing; and speaking, writing, presenting).

- Ensure that your students have lots of meaningful exposure to the language (input). Provide plenty of opportunities for practice in meaningful contexts over time (output). Second-language learners need a great deal of meaningful repetition in order to acquire and produce a second language.

- Focus on teaching high-frequency and high-interest vocabulary.

- Use formulaic expressions (standard phrases) as first steps.

- At levels 1 and 2, keep the focus initially on listening and speaking competence.

The New Zealand Curriculum recognises te reo Māori as a taonga and an official language:

By understanding and using te reo Māori, New Zealanders become more aware of the role played by the indigenous language and culture in defining and asserting our point of difference in the wider world.

The New Zealand Curriculum expresses the vision that students will be confident and actively involved lifelong learners. The teaching and learning of te reo Māori has a significant role to play in achieving this vision. All students have the potential to achieve when learning te reo Māori. As your students work towards the achievement objectives set out in Te Aho Arataki, they will also be developing the key competencies set out on pages 12-13 in The New Zealand Curriculum.

These include:

- relating to others as they participate in communicative reo Māori learning tasks (relating to others)

- using te reo Māori to communicate (using language, symbols, and text)

- participating in Māori cultural activities (participating and contributing)

- becoming increasingly autonomous learners as they acquire second-language learning strategies (managing self and thinking), such as learning from errors, using dictionaries, coining new words, making intelligent guesses from context clues, and noticing word families.

He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora is designed to support you and your students to become better communicators of te reo Māori, improving your fluency and accuracy in, what is for many, a different cultural milieu.

To achieve these outcomes, build on your students' prior knowledge, interests, aspirations, strengths, and language-learning needs by:

- constantly monitoring the teaching and learning that takes place

- encouraging your students to reflect on their own learning

- using assessment information to inform the next teaching and learning steps

- integrating tikanga appropriate for the classroom

- facilitating authentic Māori language-learning tasks

- using an inquiry learning approach (see pages 19–21 in Te Aho Arataki).

The learning contexts in He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora are set out below. They are aligned with topics in Te Aho Arataki. Exploring them will help your students to meet the achievement objectives in Te Aho Arataki.

| Learning contexts in He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora | Topics in Te Aho Arataki |

|---|---|

| Ko au (I, me, myself) My whānau/hapū/iwi (including pepeha, whakapapa, and place names); my marae/home; my friends; my community; my pets | Whānau, hapū, iwi (L1) My home (L1) Origin/identity/location (L1) Whānau relationships (L2) Roles and duties in my home/school/community (L4) |

| Taku akomanga (My classroom) Classroom objects; colours; describing things; greetings and farewells; states of being; giving and following directions; the language of classroom management; modes of transport and other related contexts, for example, mahi tahi (working together) and whakapai ruma (tidying the room) | My classroom (L1) My school (L1, L2) Modes of transport (L3) |

| Kai (Food) Meals; supermarket shopping and related contexts, such as the food for a barbecue or hāngi; kaimoana | Food preferences (L2) Planning and shopping (L4) |

| Te huarere (The weather) Weather and seasons | Weather; seasons (L2) |

| Hauora (Health) Healthy food; sports and leisure activities | Sport and leisure gatherings (L3) Planning leisure-time events (L3) |

| Ngā tau (Numbers) The numbers to one hundred; telling the time; days of week; months of the year; money | Telling the time (L4) |

| Ngā hākari (Celebrations) Matariki and birthdays | The marae: its people and places (L2) Marae routines and procedures (L3) |

Once you have selected a learning context to explore with your students:

- gather and organise the resources you need well in advance

- practise pronunciation beforehand and get to grips with the relevant vocabulary and grammatical structures. You could do this with other teachers, supporting one another

- select the learning intentions that are appropriate for your students

- familiarise yourself with the reomations, tasks and activities, transcripts and resource sheets associated with the unit, and work out how to maximise their use. Adapt tasks and activities from other units, where appropriate

- watch relevant video clips to see other teachers in action, facilitating a selection of the tasks

- consider the associated tikanga (and seek advice about this if you need to)

- look for opportunities to integrate the content of a unit into other learning areas.

The time you take to explore a learning context will depend on your students' entry points and their progress.

Use the tasks and activities in the eight units to help your students use te reo Māori in authentic contexts. The design of these tasks and activities is guided by the achievement objectives of Te Aho Arataki, using an inquiry approach.

As you facilitate the tasks and activities, monitor your students' learning, look for ways to help them progress, and reflect on how your teaching is impacting on their learning. Focus on what to teach next, how best to teach it, and what the evidence base is for your decisions (see Absolum, M. et al [2009], Directions for Assessment in New Zealand and page 40 in Te Aho Arataki).

Effective tasks are those that help learners to retain the meaning of a new word, by requiring them to:

- understand or use the word

- search out its meaning (rather than just being told)

- evaluate the word in terms of when it is appropriate to use it in a particular context.

Effective tasks and activities include dictionary searching, vocabulary exercises, writing, negotiating meaning (as in a two-way task like a dycomm), and interacting with others (where there are elements of both input and output). Less effective tasks are those where the meaning is simply given to the students – with no expectation on them to explore the words or use them.

In the eight He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora units, the tasks and activities are differentiated so that the teaching and learning is appropriate to years 1–6. We recognise that many of your students will be achieving at curriculum level 1 (the entry point for a student with no prior learning) or level 2. We also recognise that there are varying degrees of cognitive ability, literacy skills, and maturational development across years 1 to 6. The tasks and activities in the units are only suggestions. You can adapt them to use across more than one learning context. We have included suggestions about making the tasks more, or less, challenging. Use these suggestions to ensure that you meet the learning needs, interests, and aspirations of your students so that each of them can reach his or her potential when learning te reo Māori.

The tasks and activities will enable your students to:

- practise and consolidate basic te reo Māori skills

- become autonomous learners of te reo Māori

- engage in real communication while participating

- have fun while they are learning te reo Māori

- assess their progress in learning how to communicate in the language.

The tasks and activities are designed to enable your students to learn te reo Māori by taking part in meaningful communicative learning experiences, as opposed to focusing on the grammar of te reo Māori. The emphasis is on the message they are conveying, rather than the form in which the message is said or written.

Resource sheets are provided for many of the tasks. They are available online and can be adapted for use beyond the tasks they were originally designed for – across different learning contexts/topics.

Your role is to be a facilitator of the communicative process through the careful use (and design) of tasks and activities. As you facilitate, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the objective clear to my students?

- Will this task be engaging, and is it related to their interests?

- Is the task appropriate to their ability levels?

- Is it an authentic task? Does it generate a genuine communication need?

- Does it assume some knowledge of tikanga? Do my students have this knowledge?

- Will this task help the students rehearse for the real world?

- Will it help them to practise a skill?

- Will it help them to increase their fluency?

Task types

The tasks and activities included in He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora use strategies that have been found to be particularly useful for teaching and learning second languages. These include cloze tasks, dycomm (or information gap) tasks, information transfer tasks, multi-choice tasks, strip stories, same-different tasks, dictocomps, listen-and-draw tasks, true-false-make it right tasks, and 4-3-2 tasks.

Multi-choice task

For a multi-choice task, you need to design different descriptors to accompany a picture so that your students have to discriminate which descriptor best applies to the picture.

Cloze task

A cloze task requires students to fill in gaps in a text. There can also be picture clues. You can make a cloze more, or less, challenging. It could be that every nth word is deleted – or a particular part of speech is missing (for example, nouns, verbs, prepositions, pronouns, or adjectives). Alternatively, you could indicate the number of letters in the missing word, supply the first letter, or provide a list for the students to choose the words from (though not in order). You could also make a progressive version, where more words are missing each time the students do the cloze. This last technique is a useful way to give your students repetitive exposure to a new language structure.

A cloze task can be aural-oral, where you read a piece of text and stop where a word needs to be added, so that the students can suggest the correct word to fill the gap.

Once your students are experienced with the cloze technique, they can make up their own clozes for their peers to complete. The advantages of a cloze task are that it is good for attending to grammar as well as improving the students’ prediction skills and encouraging them to make intelligent guesses from context cues.

Dycomm

Another type of task is a dycomm (also known as an information gap task), where students have different, but essential, bits of information needed to complete a whole task. Dycomms allow for meaningful communication because each person has unique information so there is a genuine reason to communicate. The students must combine their knowledge and use te reo Māori communicatively to fill in the information gaps to get the whole picture. Dycomms do not need to be done in person. You could get your students to take part in one using email, txt, or Skype. The key thing is that they negotiate meaning with each other.

Information transfer task

An information transfer task requires students to put written text into pictorial form – or the converse (for example, a chart, grid, diagram, picture, or diary). Such tasks encourage deep processing of information because students have to show they have understood information well enough to adapt it.

Strip story, picture dictation, strip-picture tasks

To make a strip story, simply cut a piece of text into strips and give each student one strip to read and memorise. Then get the students to work together, orally, to order the text. The strip-story technique can be simplified so that the students are allowed to keep their allocated piece of written text while they work with their peers to put the whole text in order.

Another (more difficult) variation is to cut each strip of the text in half – getting the students to first join the two halves and then reorder the text sequentially. A variation for younger students is to provide picture clues to complement the words. On one strip, show some words and on the other a matching picture. Dialogues can also be used as strip stories.

Similar to a strip story, but easier, is picture dictation – a listening activity where you read out some text and the students must sequence the associated pictures.

A difficult variation of the strip-story task is the strip-picture task, where a whole picture is cut into strips, such that students have to describe their strips of the picture. By communicating with each other in te reo Māori, they work out how the strips fit together to make the whole picture.

Same-different task

Your students can work in pairs on a same-different task. This requires two sets of numbered grids (Set A and Set E) depicting pictures – some of which are the same across both sets and some different. One student is given Set A and the other Set E. The task is for them to communicate with each other, box by box (starting from box number 1), to determine which boxes are identical (“he rite”) and which are different (“he rerekē”).

The task could be made more complex by having pictures of the same item in Set A and Set E but with different characteristics. For example, both sets could show a picture of an apple, but one could be green and the other red, so that the students have to not only name the item (“he āporo”) but describe it too (“he āporo kākāriki” and “he āporo whero”).

Dictocomp

Another useful task is the dictocomp, where you read out (twice), at normal speed, a simple piece of text in Māori. During the first reading, the students listen. In the second reading, you pause between the sentences so that the students can jot down rough notes (in English or te reo Māori) about the key content. The job thereafter is for the students to work in small groups and, using their own and other students’ notes, recapture the key points in the text. In a dictocomp, you could choose to deliberately focus on a particular sentence pattern to reinforce that construction. A dictocomp need not be aural. You could give students the text to read and then remove it before asking them to reconstruct what they had read.

Listen-and-draw task

In a listen-and-draw task, each student (in a pair) could have a numbered grid comprising nine squares, with pictures in different squares. Each partner has to tell the other student what pictures to draw in the empty boxes so that, by the end, both grids are identical. Helpful language for this task includes:

| Māori vocabulary | English translation |

|---|---|

| pouaka | box |

| kei roto i te pouaka | in the box |

| nama | number |

| tapawhā | square |

| tuatahi, tuarua, tuatoru | first, second, third |

| kei roto i te pouaka tuawhā | in the fourth box |

| Tuhia ... | Draw ... |

| he | some, a |

| Tuhia he āporo. | Draw an apple. |

| Haere ki te pouaka tuarima. | Go to the fifth box. |

True-false-make it right task

In a true-false-make it right task, the students have to listen carefully and state whether each of the statements they hear (or read) is true (“Kei te tika”) or false (“Kei te hē”). Then they have to go one step further and correct any erroneous statements by giving the right form.

4-3-2 task

The aim of a 4-3-2 task is to build the students’ fluency in te reo Māori by getting them to repeat a short talk, to different partners, using language that is familiar to them. They have four, then three, and then two minutes (or whatever amount of time is realistic for your particular students) to do so. Their focus is on the message (not the grammatical structure of the language). This task is challenging because, at each repetition, the students have to deliver their talk in a reduced time. As a variation, you can ask the listeners to take brief notes or jot down questions to ask later. The listeners could then compare the contents of the talks they heard. Another variation is for students to record themselves (instead of talking to a partner). They could then listen to their recording, make notes of any improvements they can make, and then record themselves again until they have their best recording.

For more information about some of these key second-language teaching and learning tasks that feature in HeReo Tupu, He Reo Ora, see the section Te Whakaipurangi Rauemi on Te Kete Ipurangi.

In addition, there are resource sheets on the website to support many of the tasks in He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora.

Assessment is integral to the teaching and learning process. It is an ongoing process in which you and your students:

- determine where they are in their learning journey

- reflect on how the teaching and learning process is supporting their acquisition of te reo Māori

- work out ways to progress (the next learning steps).

This cyclical, shared process acknowledges the Māori concept of ako, with its underlying premise of reciprocity in teaching and learning and its notion of inseparability between learner and whānau.

To be effective, the assessment you do needs to involve and benefit your students. In second-language learning, students need sufficient opportunities to encounter new learning in different contexts and on multiple occasions. Assessment will help you and your students to determine what constitutes "sufficient opportunities" so that learning experiences can be sequenced over time.

Much of the assessment of learning will be "of the moment", providing useful information on student achievement. Plan any formal assessment and share all information with your students. Ensure that the assessment is fit for purpose, valid, and fair. Students are the prime owners of their assessment results. They need this information to determine, with you, where they are with their learning and where they need to go to next. The process of gathering evidence gives you insights that will shape your practice. It gives your students insights that will shape their learning.

Students need to understand the significance of the assessment feedback they receive, and what to do next.

(Absolum, M. et al, 2009, p20.)

Adopt classroom practices that exemplify this kind of formative assessment:

- Share the learning intentions and success criteria with your students so that they understand what is expected of them and are able to monitor their progress against these expectations.

- Give your students targeted and specific assessment feedback on their learning, using clear learning intentions and success criteria. In this way, they will have a stake in their own learning and assessment and will be involved in working out the next learning steps. This will impact on their motivation and achievement.

- Create opportunities for self-assessment and peer assessment to increase the students' assessment capabilities and their awareness of progress.

- Share assessment information with whānau so that they gain a better appreciation of their children's strengths and needs in learning Māori. Engaging with whānau has a positive impact on student achievement.

- Use the suggestions for assessment in He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora and Te Aho Arataki (see pages 56–70) to monitor student progress. If you are teaching younger students, your assessment practices will be mainly oral-aural.

- Use pair and group assessment opportunities where each student's contribution is valued and every student participates to his or her full potential.

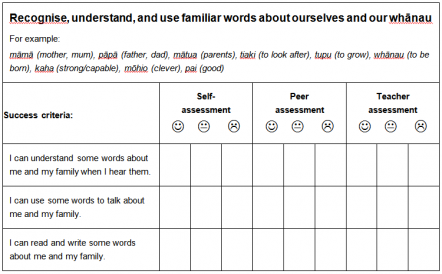

One way to record progress is to use an assessment rubric. You will find one in each unit. There are spaces for student self-assessment and peer assessment, as well as the assessment you will be doing. Your students will use these to monitor their progress, identify areas that need further practice, and work out their next learning steps – in consultation with you. Adapt and modify the rubrics in the units to the age and achievement levels of the students in your class.

You could also make audio and video recordings of progress over time and use these to monitor improvements in fluency and accuracy.

Possible learning intentions and success criteria are included in the assessment rubrics, presented in each unit. You and your students can develop these together. When students construct with their teacher the success criteria for a particular piece of learning, they develop an understanding of the standard of work required, and the extent of the learning required. This assessment format can be used (or adapted) by students and teachers to assess and monitor progress over time.

Some success criteria may develop into separate learning intentions in their own right as you and your students discover aspects of the criteria that need further exploration. The success criteria are included as a guide only. Ideally, you will share the learning intentions with your students and will work with them to develop appropriate success criteria.

Learning intentions and success criteria will ensure that the students clearly know what is expected of them and what success will look like. This helps the learners to monitor their own progress, enabling them to make the most of feedback from you about how they are progressing and what could be the next appropriate learning steps.

The learning intentions have been formulated to provide you with opportunities to explore all the modes of language identified in the achievement objectives in Te Aho Arataki (listening and speaking, reading and writing, and viewing and presenting). At curriculum levels 1 and 2, put more emphasis on listening and speaking (and viewing and presenting, where appropriate).

It is not intended that the learning intentions reflect a learning progression across the curriculum. Different levels of difficulty are inherent in the tasks that support the learning intentions – to give you flexibility to meet your students' needs.

You might like to use the following rubric as a template. Each unit has a set of rubrics you can download under "Learning Intentions and Success Criteria".

Instead of smiley faces, you could use traffic lights. See what your students suggest.

Learning intentions for extension

There are additional ideas in each unit for extension learning. Use these suggestions when you are working with students who are capable of achieving at curriculum levels 3 and 4. These are not exhaustive lists. Work with your students to determine the actual learning intentions that will extend their learning. They will contribute their own ideas. Work with them to develop appropriate success criteria.

Few of us can remember acquiring our first language, yet almost all of us learn our first language without being at school. We succeed because this is a meaningful experience that is guided by our whānau and our friends. These people model our first language, and they accept that we will make mistakes. They know, and indeed expect, that we will succeed.

When learning a second language at school, the experience is different. Second-language learning at school needs a more deliberate, organised approach. The guiding principle of successful second-language teaching at school is that students learn best when they can see a real point in what they are doing and saying. They need to communicate real information for authentic purposes. A genuine desire to communicate needs to drive their learning.

In our first language, there is a correlation between the number of words we know and our ability to communicate (including our ability to read and write). The same is true for second-language learners; hence the importance of vocabulary development. As with our first language, listening and speaking come first. We will explore vocabulary development in more detail later in this resource.

The title of this resource, He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora, reflects growth through the levels of Te Aho Arataki, from te whakatōtanga (levels 1–2) ki te tupuranga (levels 3–4) ki te puāwaitanga (levels 5–6), tae atu ki te pakaritanga (levels 7–8) – that is, from a sapling to a fully flourishing tree.

It also reflects a belief about the well-being of te reo Māori – that it will survive if we expand the variety of domains where it is used. Primary schools have a significant part to play in this. The education system is a main artery supporting intergenerational transmission.

Just as learning te reo Māori at home and in early childhood settings builds a solid foundation for further learning at primary school, He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora aims to provide a strong platform for learning te reo Māori in years 1–6 so that there is a seamless transition to learning te reo Māori in years 7-8. The learning progression in Te Aho Arataki, through eight achievement levels, provides this continuity and sets out incremental learning steps to achieve it. At years 7–8, Ka Mau te Wehi! provides a similar strong platform for learning, allowing a seamless transition to learning te reo Māori at secondary school.

He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora mainly supports teaching and learning at curriculum levels 1–2, the entry point being level 1 for students with no prior knowledge, regardless of their school year (see page 24 in The New Zealand Curriculum). There are extension opportunities for students achieving at levels 3–4. Use this material to support students whose prior learning of te reo Māori provides a foundation for learning at these levels.

He Reo Tupu, He Reo Ora is also designed to support you as a teacher of te reo Māori , even if you do not know much more than your students.